The Cantor-Schröder-Bernstein theorem

Definition

If \(A\) and \(B\) are sets with \(|A| \leq |B|\) and \(|B| \leq |A|\), then \(|A|=|B|\). In other words, if there are injections \(f:A \longrightarrow B\) and \(g:B \longrightarrow A\), then there is a bijection \(h:A \longrightarrow B\).

Proof

This theorem seems to be straightforward and one might expect that is has an easy proof. However, no known proof of this theorem is ”easy” to explain, even without using advanced mathematics. To put this into perspective, Ernst Schröder (whose name appears in the theorem title) published a flawed proof in 1898.

To provide a more interesting perspective on the proof of the theorem, we will make use of Hilbert’s Grand Hotel paradox, a famous thought experiment formulated by German Mathematician David Hilbert. It shows the counter-intuitive properties of infinite sets. Hilbert used it as an example to show how infinity does not act in the same was as regular numbers do.

Hilbert’s paradox: Hilbert invented the notion of the Grand Hotel, which has a countably infinite number of rooms, each occupied by a guest. However, when a new guest arrives, it is always possible to find a room for this guest without evicting a current guest from the hotel. The paradox here is that even though the hotel was initially fully occupied, it can always make room for additional guests without evicting current guests.

Because the rooms of the Grand Hotel are countable, we can list them as room 1, room 2, room 3, and so on. When a new guest arrives, we move the guest in room 1 to room 2, the guest in room 2 to room 3, and in general, the guest in room n to room n + 1, for all positive integers n. This frees up room 1, which we assign to the new guest, and all the current guests still have rooms.

Similarly, if a countably infinite number of new guests arrive, we move the guest in room \(n\) to room \(2n\). This frees up all the odd number rooms \((2n − 1)\), which can then be occupied by the infinite number of guests.

When dealing with a finite number of rooms in a hotel, the notion that all rooms are occupied is equivalent to the notion that no new guests can be accommodated. However, Hilbert’s paradox of the Grand Hotel can be explained by noting that this equivalence no longer holds when there are infinitely many rooms.

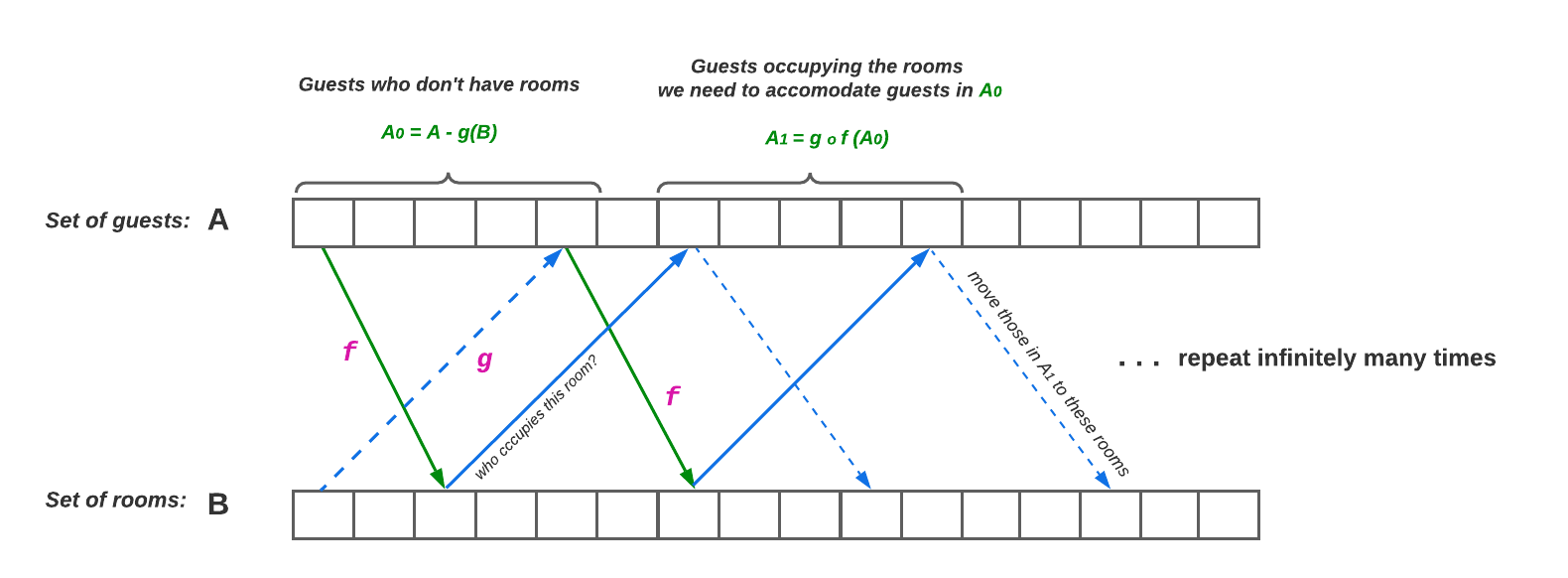

Now, going back to the original Cantor-Schröder-Bernstein (CSB) theorem, we can draw a connection between Hilbert’s infinite hotel and the theorem by considering set A as hotel guests, and set B as rooms in the hotel. Our objective is to map each guest to a distinct room (ensuring that no two guests share a room) and ensure that all the rooms are occupied at the end of the process. In other words, we want to construct a bijection between sets \(A\) and \(B\). Function \(f\) associates a guest to a room, while function \(g\) tells us which guest occupies a specific room.

We shall focus on set \(A_0 = A − g(B)\), the new guests who don’t have rooms yet. That is, the elements of \(A\) that are not in the image of \(B\) under \(g\). We can find rooms for them using \(f\) with the mapping: \(f(A_0)\). However, there could already be guests occupying the rooms \(f(A_0)\), so we will need to move these guests \(A_1\) to new rooms. But first we need to know the guests to be moved by using function \(g\) which gives us: \(A_1 = g(f(A_0))\). Similarly, we can use f to find rooms for them by doing \(f(A_1) = f(g(f(A_0)))\), and we will repeat this infinitely many times. We can formalize this to obtain the following definitions:

\(A_0 = A - g(B)\)

\(A_{n+1} = gf(A_n)\)

\(A_\infty = \bigcup\limits_{n=0}^{\infty} A_n\)

We can then define \(h:A \longrightarrow B\) as follows: \(\begin{cases} f(x) & x\in A_\infty\\ g^{-1}(x) & x\in A-A_\infty \end{cases}\)

What this means in terms of the hotel is, if guest \(x\) is a new guest or a guest that is being displaced, we will find a room for guest \(x\) using \(f(x)\). Otherwise, if guest \(x\) is not being displaced, we will simply leave the guest in the room they currently occupy, i.e., \(g^{-1}(x)\). We just need to show that h is indeed bijective.

Showing h is injective

For \(x, y \in A\), suppose \(h(x) = h(y)\). We have 4 possibilities:

- \(x, y \in A_\infty\) : This means \(f(x) = f(y) \implies x = y\), since \(f\) is injective.

- \(x, y \in A_\infty\): This means \(g^{-1}(x) = g^{-1}(y) \implies x = y\), since \(g\) is injective.

- \(x \in A_\infty\) and \(y \in A - A_\infty\): \(x \in A_\infty\) means \(x \in A_n\) for some \(n\). So \(h(x) = h(y) \implies f(x) = g^{-1}(y)\), so \(y = g(f(x)) \in g(f(A)) = A_{n+1}\); this is a contradiction since y is suppposed to be in \(A - A_\infty\).

- \(x \in A - A_\infty\) and \(y \in A - A_\infty\): this is symmetric to case 2, and so is covered without loss of generality.

Showing h is surjective

TODO